Raha Raissnia

Press release

Xippas, Paris

March 2023

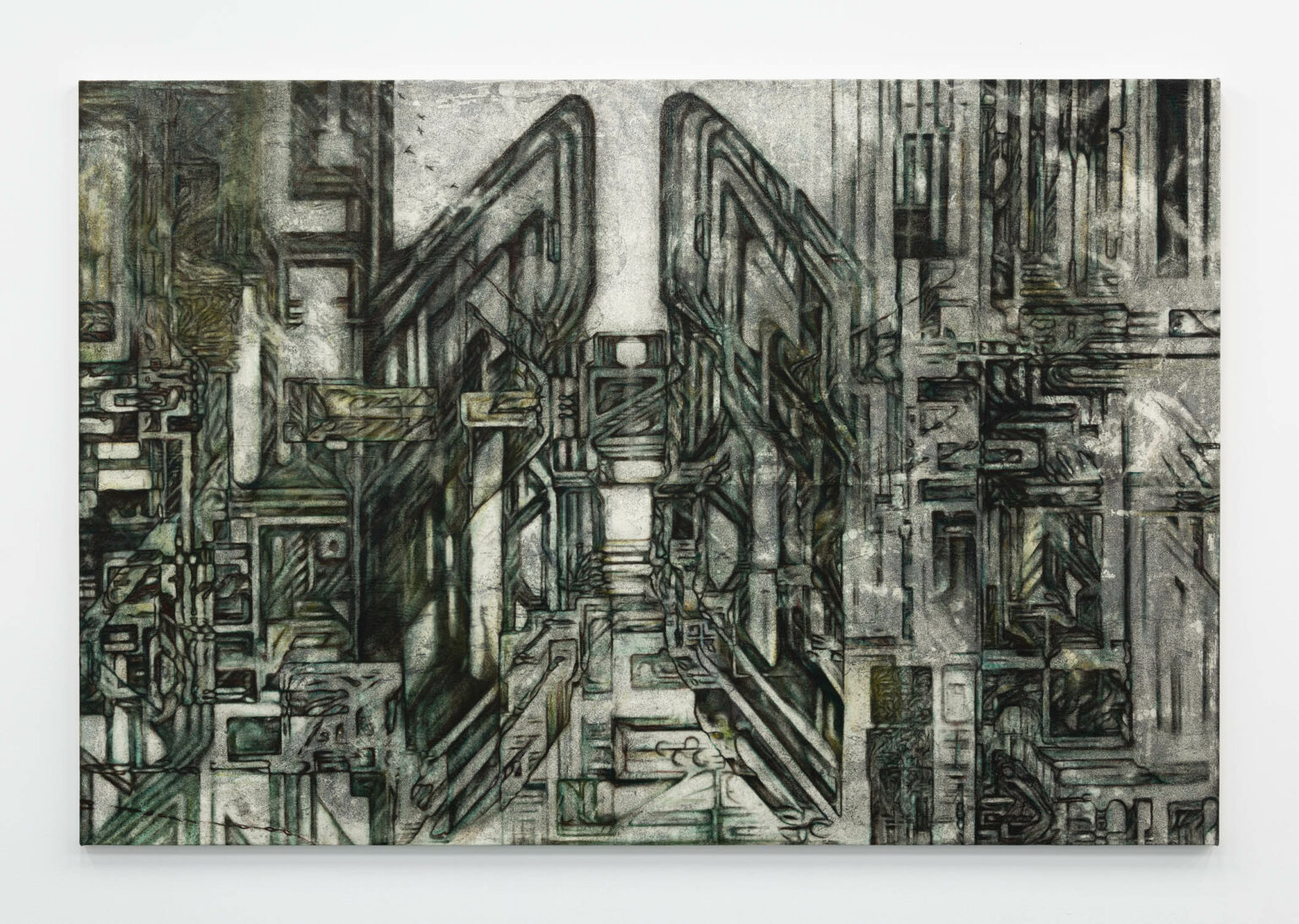

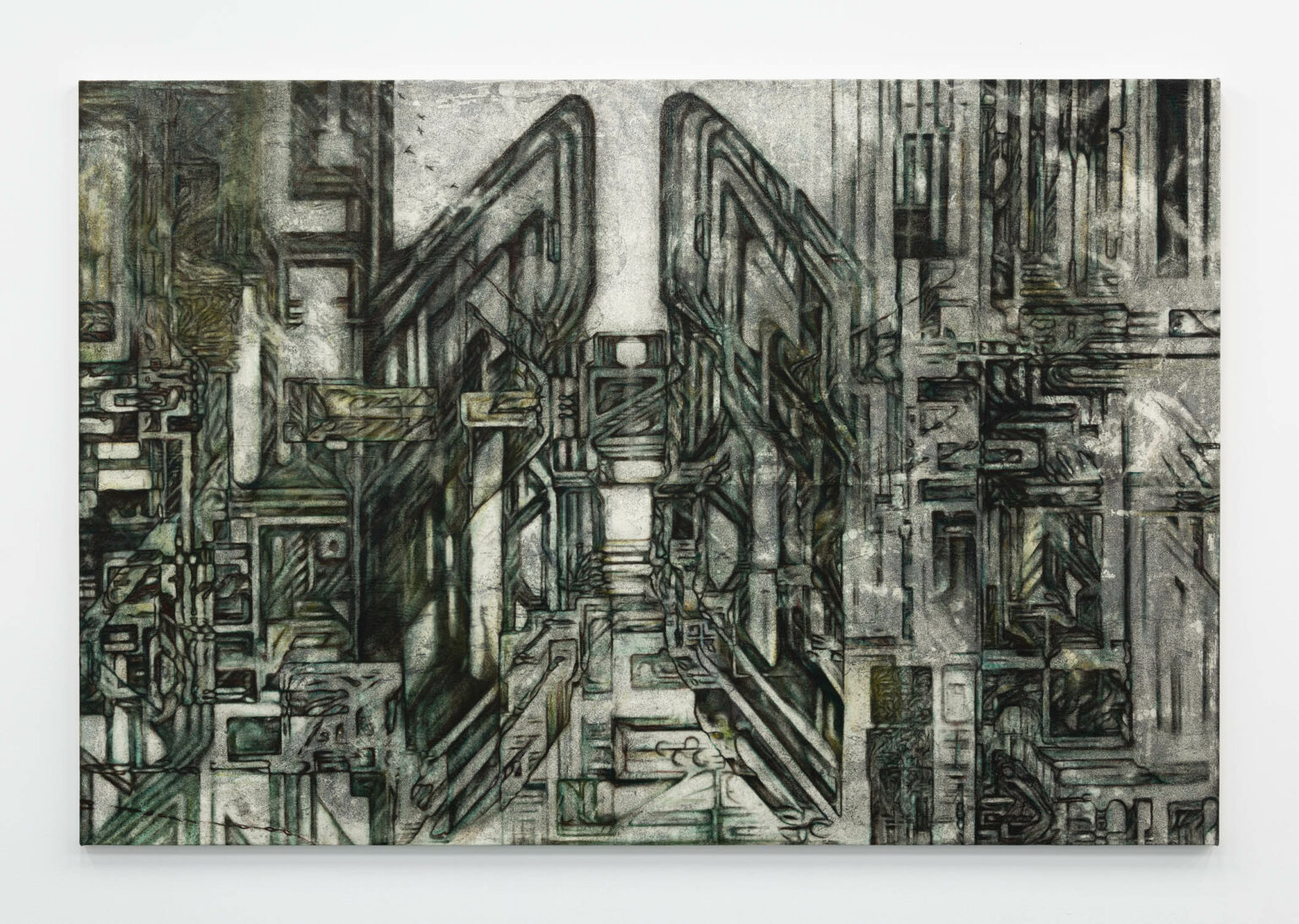

Raha Raissnia’s works of the past three years mark a significant change in her practice,

both conceptually and in terms of technique. The way she works has always been

complex, intricate and self-reflecting. Indeed, Raha Raissnia often transforms her older

drawings into paintings, reinterpreting them anew, like musical themes in a session

of partially controlled improvisation. Thus, she transfers onto canvas already existing

shapes - fragments of her past artworks, images of architecture or natural elements

like water or lava, etc., found in books and archives. Sometimes she does it freehand, more often she prints the drawings on thin transparent paper and, with help of

gel, prints the ink-crafted silhouettes on canvas, primed with several layers of gesso.

Then, she acts upon the freshly transferred forms – sanding them and painting over

them in oil or acrylic paint. What interests her in the process of transformation of one

media into another are all the possible mis-registrations and erasures, all the residues

that got ‘lost in translation’ but which, by their very absence, participate in creation of

new shapes and structures. Like excavated artefacts that might have been altered or

‘damaged’ when they are being pulled back into the present through the “wall of time”[1]

,

they only gain in preciousness. This way of producing images brings her painting closer

to an archeological operation, to an act of reminiscence instead of blind repetition that

embraces neither intuition nor chance. .

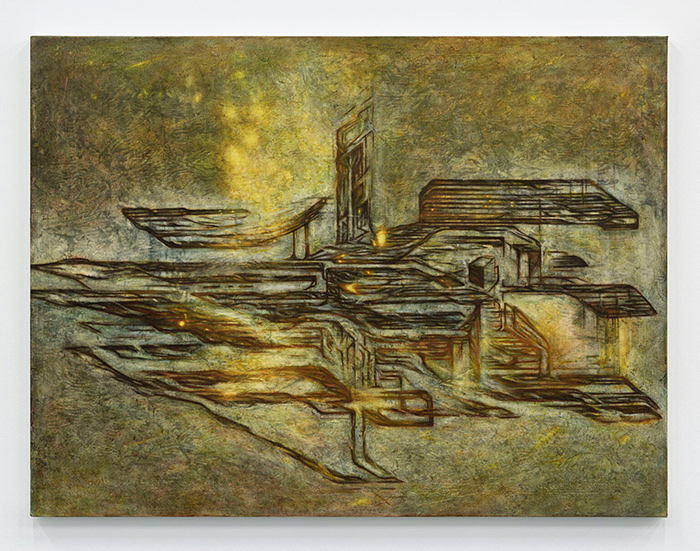

In Raha’s recent paintings, what is most striking is a fascinating presence of light and

color. The images seem to glow from within, which is paradoxical if we take into account

how this effect is obtained. In these paintings, Raha Raissnia uses grisaille, a technique

employed by the old masters. To spare the pigment, they would make their paintings in

black and white and add color only at the end, in very thin layers, ‘glazing’ the pictorial

surface and slightly ‘drowning’ it in a tinted transparent substance. Thus, the color

is confined to the pictorial surface, and one could only wonder how it is that we get

an impression that the painting is impregnated with light, as if it was spreading from

inside the image? Would it be because light, like music, is a sort of “ghostly incorporeal

being” [2]: we cannot examine it nor touch it, it is always mediated by something else,

by the things that light reveals to us, dancing upon their skin? This parallel between

light and music is very important in Raha’s work, not only because her practice is

nourished by her collaborations with the musicians and that music is essential in her

films and performances. Her painting seeks to capture a musical moment without truly

apprehending it. The abstract patterns and forms populating her works are fuguelike. They are always evolving, always ‘running’, and seem to develop intuitively by and

from themselves, building rhizomes and mazes. As if they were hoping to reach Plato’s

ultimate ‘reservoir’ of shapes and ideas, a place from which all forms come from – or, in

artist’s words - the beyond.

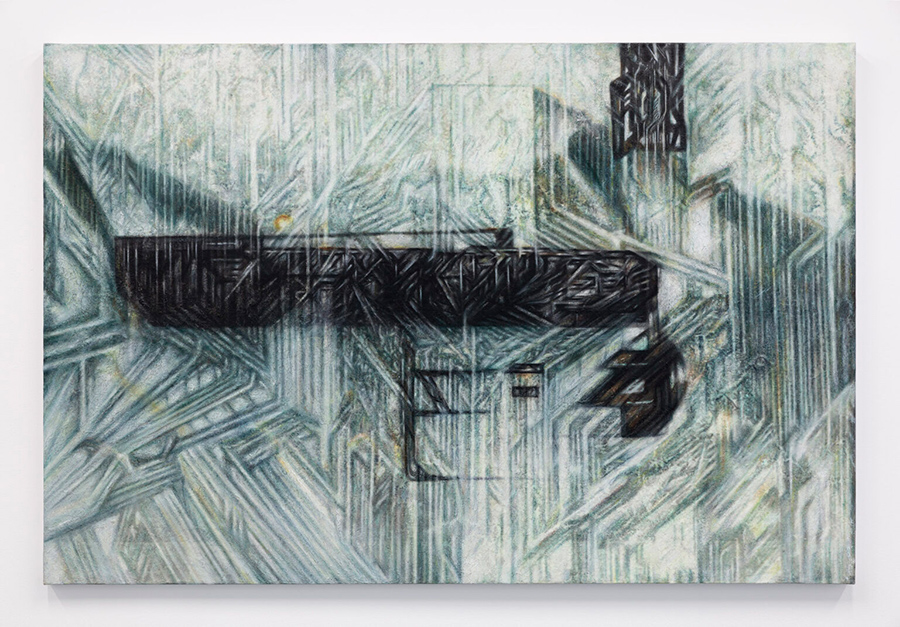

Concerning the subject matter of her paintings, Raha Raissnia remains loyal to the

theme she has developed over years: the human condition and the beauty of its fragility.

Thus, in the midst of abstract interlacing patterns, we see shadows of the man-made

world. These allude to the technological and architectural elements of her vocabulary,

giving shape to a dream of some biomorphic future. Her paintings look both ancient and

futuristic, crossing multiple timelines and incarnating the very idea of time which, if we

are to repeat Heidegger’s argument, isn’t in itself temporal but which makes other things

temporal [3]. Raha’s images seek something similar: to mix temporal with a-temporal,

understanding time both as history and thus change, and as an idea.

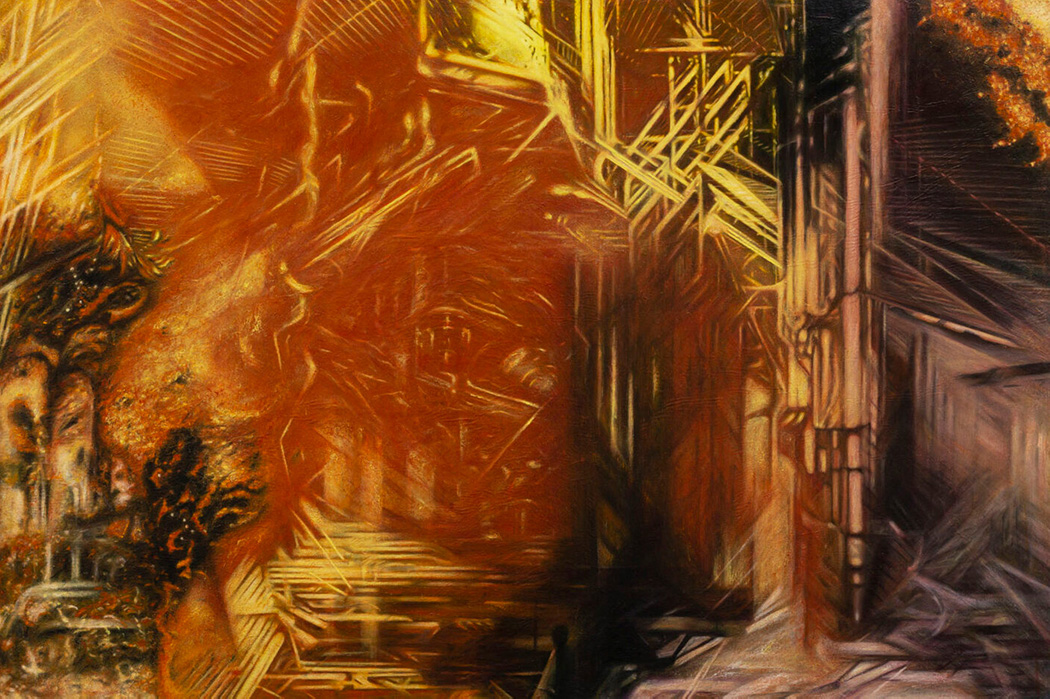

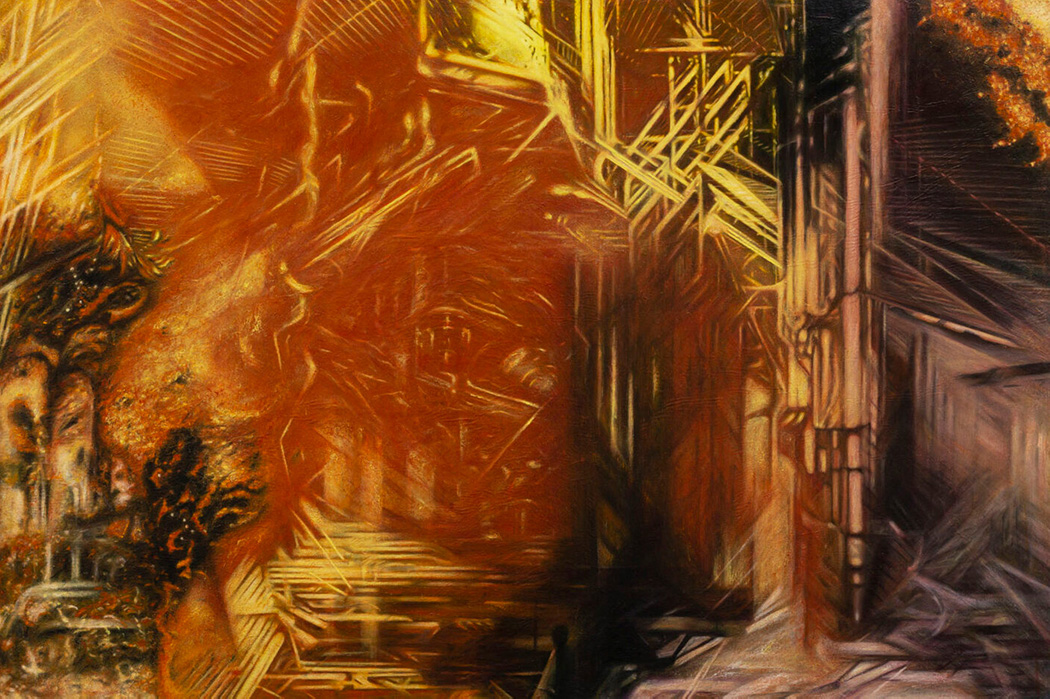

What has shifted in Raha’s vision, is that there is now a certain apocalyptic feeling to it.

Her recent works talk more openly about humanity in crisis, about the carelessness of

our technological ways, pushing us towards an ecological, social, political catastrophe.

They picture a world caught in flames (Nightshades, 2022) or a civilization in ruins, with

nature taking over the artificial kingdom of men (Iridium, 2020). They capture evanescent

architectural structures in the process of self-erasure (Hypogynous, 2020) – or what appears

to be a spaceship, again on fire (Massicot, 2020), as it leaves this world,

accelerating towards a new one. Most importantly, they all incarnate movement and

convey a certain sense of urgency, adding purpose to a sophisticated postmodern play

of abstract shapes and forms.

The invocation of light mentioned above also plays its part. Indeed, despite their evident

tenebrous ambience, Raha’s paintings are far from being pessimistic. Rather, they seek

to discover beauty in the midst of ruins and darkness, just like they seek to find hope

there. As she admits it herself, her recent works have been influenced by the writings

of the poet and philosopher Jason Bahbak Mohaghegh[4], whose labyrinthine reflections

don’t only explore the somber territories one may cross before arriving to a thought of

a possible omnicide, but also seek to imagine what “happens creatively”[5] in the face of

destruction (by analyzing, among other things, the writings of prisoners condemned to

death). This desire to condense one’s experience in a poetic formula, desire to transfer,

to transform and to share, saving some inner knowledge or memory from oblivious

darkness, is something very human. And it is this same desire that illuminates Raha’s

visual poetry. Thus, the painting Headlong, 2020, might simultaneously tell a story of an

exploding sun and of “a time of fossilized dawns”[6], whilst also announcing the birth of

some new universe. After all, it is not uncommon for a world to be built on a corpse of a

murdered god (exactly as happened to the Babylonian god Abzu). Only thus could it be

created (reformed, reborn, reformulated). Rising from the dead and from the ashes –

phoenix-like.

Raha Raissnia (with James Siena), Xippas Paris, 2023

All images courtesy Xippas, Paris

Born in 1968 in Tehran (Iran), Raha Raissnia lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

In 2017-2018, Raha Raissnia had a personal exhibition at the Drawing Center (New York).

In 2016, her work was the subject of a solo presentation at the Museum of Modern Art (New York)

and in 2015, Raissnia’s work was included in All the World’s Futures of the 56th Venice Biennale.

Previously, her work has been featured in exhibitions at the MOCA (Los Angeles), CSS Bard Hessel

Museum (Annandale-on-Hudson, New York), Drawing Lab (Paris), Museum of Contemporary Art St. Louis,

The Kitchen (New York), the Isfahan Museum of Contemporary Art (Isfahan, Iran). Raissnia’s projection-performances

have been held at the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York), REDCAT (Los Angeles), Arnolfini – Center

for Contemporary Arts (Bristol, UK), Issue Project Room (New York), Emily Harvey Foundation (New York)..