L: Peter, thank you so much for accepting the invitation to talk – it is always so pleasurable

to get lost in conversation with you!

PETER HALLEY: Yes, it’s very nice to have a conversation with you, Lena. I should tell our readers that

we met a few years ago in Paris and that you contributed wall texts for my installation in Venice, Heterotopia I,

in 2019. Since that time, especially when we were all isolated during Covid, we have had a number of long phone

conversations about my work. So our readers are stepping into a dialogue that has been going on for a long time.

L: Let’s discuss the evolution that has been taking place in your work over the past few years. In general,

your practice, the whole legacy that you have been building since the 80s, resides upon two major principles: repetition of

your iconic three-element prison-cell-conduit structure, and alteration.

P: Yes, that is really central to the way I work. I think there are two things going

on in my work at the same time. On one hand, the actual internal mechanics of the work are very important

to me. I have these three iconic elements. They are flat geometric shapes that rest on an uninflected flat

ground. It is a very literal two-dimensional world. The shapes do not overlap to create any illusion of

depth. The cells, prisons, and conduits are built up in low-relief texture so they sit on top of the canvas ground.

That’s very literal as well. On the other hand, this absurdist iconography emerged from my obsession with the nature

of social space in our world. I am still convinced that the space of our whole civilization is characterized by

isolated terminals connected by technologically determined conduits. It dominates our physical space, our

communications space, our organizational space, and our intellectual space.

L: Naturally, since the world

was changing, your paintings should have been changing all along, responding to the changing context. And they

indeed have. The artworks from the late 80s are marked by the sense of isolation. Those from the 90s suddenly

become all glossy, absorbing the world’s ‘glamour’ state of mind. The proliferation of conduits in the compositions

of this same years reflects to the explosion of the Internet.

P: Somehow, in forty years I haven’t gotten tired of playing with these three elements. Perhaps that’s because,

to me, there is also a psychological element. To some extent, I see these prisons and cells as characters on a stage.

I’m interested in how they connect or don’t connect, what kind of narratives emerge.

L: Despite the obvious continuity in your work, your practice has been marked by several disruptions,

or, I prefer to say, revolutions. One of these happened in 2015 when you started to make your

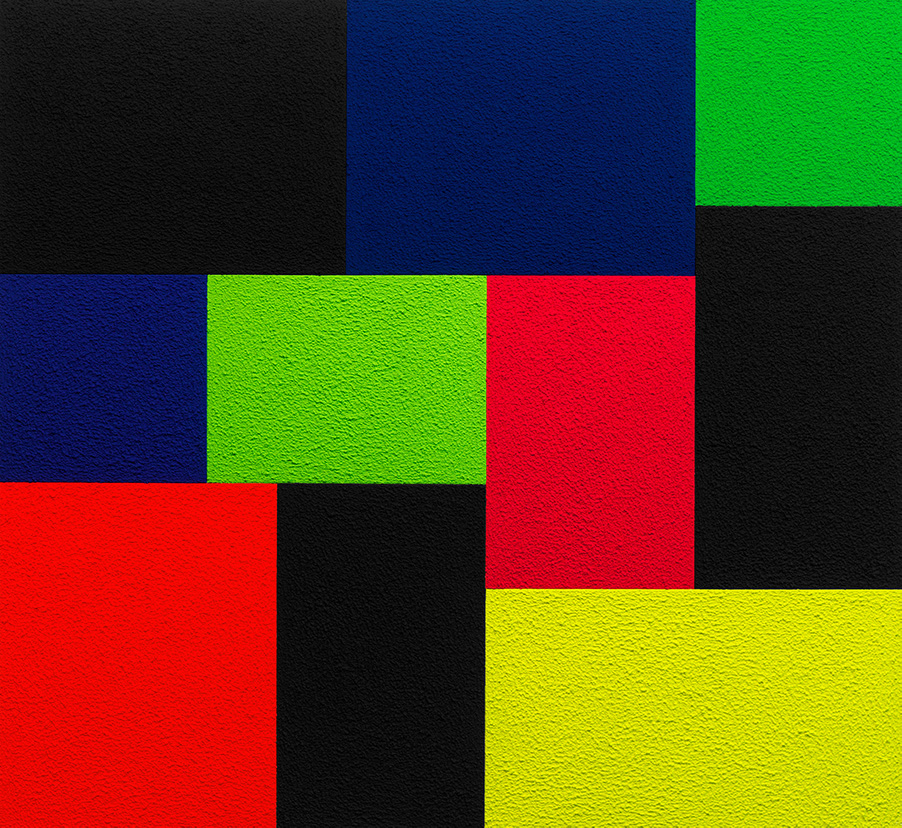

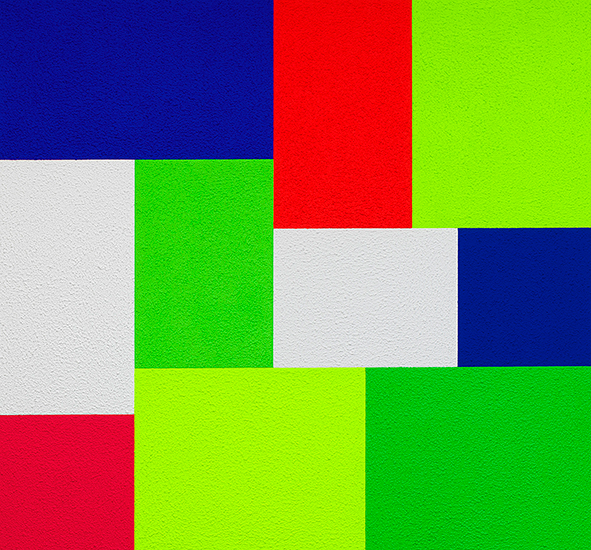

CELL GRID paintings that are currently on view in Dallas Contemporary. What is striking is that

they are composed out of only one structural element: the cell.

P: These paintings are built out of rectangular cells of different sizes, which you can think

of as rooms or containers, that are squeezed side by side into a rectangular format. The paintings are very

physical: each cell is a different canvas bolted to the next. They are also very tactile, since they are homogeneously

covered with Roll-a-Tex to create a uniformly rough surface. There are no figure ground relationships and of course

no conduits connecting the cells. As wireless connections have recently become more ubiquitous, it seems I got the

idea to leave the conduits out of my paintings.

L: First, I saw in them a general tendency towards simplification. Then I realized that there

is a hidden dimension: these paintings create a fold in a fold. By a fold I mean a Deleuzian fold that creates

an inflection of sense, making the arrow of meaning suddenly change direction and go the other way around. Like

folds in baroque drapery.

P: There is indeed a certain simplification in the elementary structure. However, when cells

are staked together, they create a grid. The grid is not visible as a separate component of the composition,

like in my other paintings, but it is still there. It encapsulates the cells and defines the composition.

Such alchemical transformation of a cell into a grid implies an inflection of meaning, a broadening of

meaning. Through this, I wanted to ironically invert the idea of simplicity.

L: The paintings as objects got more complicated as well. The number of canvases, all bolted together,

has significantly increased.

P: I imagined a process in which cells duplicate and multiply, reinforcing their physicality.

Such mechanisms – accumulation of parts, creation of masses of matter – are, in their spirit, very baroque.

So your allusion to Deleuze and his baroque drapery resonates with me. I guess I wanted to see how the same

mechanisms would behave, if, say, they were transposed in a modern, geometrically rigid, very Cartesian context.

L: Some of the grid-paintings explore shades of one color. Others are colored in primary colors and

play with visual contrasts, reinforcing the push-and-pull effect, like the paintings titled “Solace” and "The Choice”

in your current show at the Dallas Contemporary.

P: Oh, yes. These two in particular were a kind of pastiche of Neo-Plasticism from the 1920s. I like

calling them Pop-Art Mondrians. It has always been appealing to me to flirt with historical references. I am interested

in parody as a creative strategy, using parody and exaggerating historical models in search of a hermetic theatricality.

Ever since the 1980s, I have been drawn to Baudrillard’s notion of hyperreality. It induced me to think about

the contemporaneity in terms of simulation and science fiction. To paraphrase Robert Smithson, science-fiction

is not about the future. It is now and it is happening.

L: In his essay Entropy and The New Monuments, Smithson advances an idea that multiplication

of surfaces produces a funny effect: it kills time. In the CELL GRID paintings we witness multiplication of similar

looking surfaces, and I find it interesting, notably in relation to the question of time. Was it something you

were thinking about?

P: I am indeed interested in the concept of time. Maybe not killing time, but playing around with it. I think

artworks can either speed up time, slow it down, or take us out of time. In the 80s, I wanted to make very “fast”

paintings which would impact the viewer in a very immediate way. But I also hoped that they could function halfway

between a diagram and a riddle, both graspable, at least on some level, and elusive.

L: In the installations you have done since the mid-1990s, you have used the entire space to construct

more elaborate narratives, which changes how time functions in your work. Then in the last decade, at the Schirn

Kunsthalle in Frankfurt in 2016 and in the installation titled "Au-Dessous / Au-Dessus” at Xippas in 2018,

you created all-enveloping environments with strong narrative and temporal themes.

P: I am hoping to slow the viewer down, to engage him or her in a thorough exploration of the

relationship between the three dimensional space and the two-dimensional space of the images. In these installations,

I want to create complex interrelationships as viewers move through space and encounter images. Some of these

encounters are planned, and some random. I hope this complexity on its own can generate puzzles and unplanned

references. In 2019, I executed two conceptually interrelated installations, one taking place in Venice, the

other in New York. They were named Heterotopia I and Heterotopia II, referring to Michel Foucault’s idea of

heterotopia which he first wrote about in a short essay, “Espaces Autres,” in 1967.

L: Foucault defined heterotopias as worlds within worlds, mirroring and yet upsetting what is outside.

He provided

examples such as ships, cemeteries, bars, prisons, gardens of antiquity, fairs, schools,

temples, and many more.

P: Yes, I wanted to combine them all in the Venice installation! But Foucault also emphasizes

that a heterotopia is a place which embraces time, that makes multiple timelines coexist. But it also remains

outside of time. The very contradiction of it – of a place being time-less and time-full, moving but frozen in

motion – seemed dazzling.

L: In Heterotopia I you’ve built a whole temple-like House with multiple chambers and even a

labyrinth. A nobilified version of Disneyland, which, for Baudrillard, was a very symptomatic place. At the same time,

your installation was like a video game, magically materialized in space, blurring the frontier between virtual and physical.

P: Yes, it was an architecturally orchestrated space embedded inside a 500-year-old Venetian warehouse.

I invited three other artists – Lauren Clay, Andrew Kuo and RM Fischer – to participate and design their own rooms

within this labyrinth. And I invited you to contribute the wall texts. If one is interested in complexity, it

helps to have a polyphony of voices. Since it was Venice, the whole installation had to be packed with parodic

references to European cultural history. There was a cenotaph, a broken pediment, columns galore, hieroglyphics

made from digital copies of my drawings from the 1980s, and even an armillary sphere. But the images on the walls

were all digitally printed and the three dimensional elements were made of flimsy wallboard, so everything became

flattened and took on a virtual quality. It was like a demonic version of Disneyland, as you were saying.

L: This is why there were so many architectural references…

P: Indeed. The cartoon-like pediment at the entrance referenced Robert Venturi’s

“Mother’s House,” which is itself a suburban parody of 'the nightmare of European history,' as

the saying goes. The first room reimagined a tomb of Egyptian Queen Nefertari with my 1980s line

drawings reimagined as a logographic alphabet. The second room was a tribute to Charles Moore’s

Piazza d’Italia in New Orleans, another magnificent parodic fantasia. I first saw it right after

its completion in 1979. I was living in New Orleans at a time. I was intoxicated with revisiting

history, crossing timelines, reading the past from the lips of the present.

L: The Soma/Sema formula seemed to resonate with this vision. It has

also echoed the ideas rooted in the paradigm of surveillance capitalism, which introduces an

interesting conceptual shift.

P: I have always seen in geometry a mechanism of control, the most efficient means

of moving people and things. Cyberspace only seems to offer an escape from geometrization, but

it reinforces Cartesian binarity and creates a constantly increasing level of abstraction. In

the second half of the 20th century, the human body was reduced to numbers — a credit card number,

a social security number, etc. Today, we are surveilled constantly every time we use our phones,

which never leave our bodies. And the informational surplus is monetized by the mega-companies. In

cyberspace one is constantly watched. Virtual bodies turn into not so virtual prisons. Plato’s

formulation seems extremely relevant today.

L: Heterotopia I was followed by Heterotopia II at Greene Naftali gallery in New York. You built

a chamber, an entire house within the large gallery space. There were stairs, rooms on different levels, all

surrounding a glowing yellow core. The viewer had a chance to experience your paintings from inside out. I was

completely fascinated with the fact that in this installation you were challenging the distinction between two-dimensional

images and three-dimensional objects, making them ambivalent if not paradoxical. They became transitive, two sides

of the same coin.

P: In this exhibition, I wanted to see the characteristics of painting and architecture collapsed and

confused. The architecture is configured to frame the paintings, but at the same time the paintings act as representations

of architecture. I compose the paintings as sectional views, but they can just as easily be viewed as floor plans as well.

Then, the paintings shared the materiality of the architecture in several ways. The configurations or compositions on

the paintings’ surfaces are not just flat diagrams but have low relief surfaces made from the same kind of building materials

used as the surface finish of the physical walls around them (stucco, sheet rock paste, etc.). At the same time, in Heterotopia II,

the color palette of the paintings was also transferred onto the walls, beams, floor, and staircases that define the physical space —

a simple way to further blur the boundary between the representation of the space and the physical space.

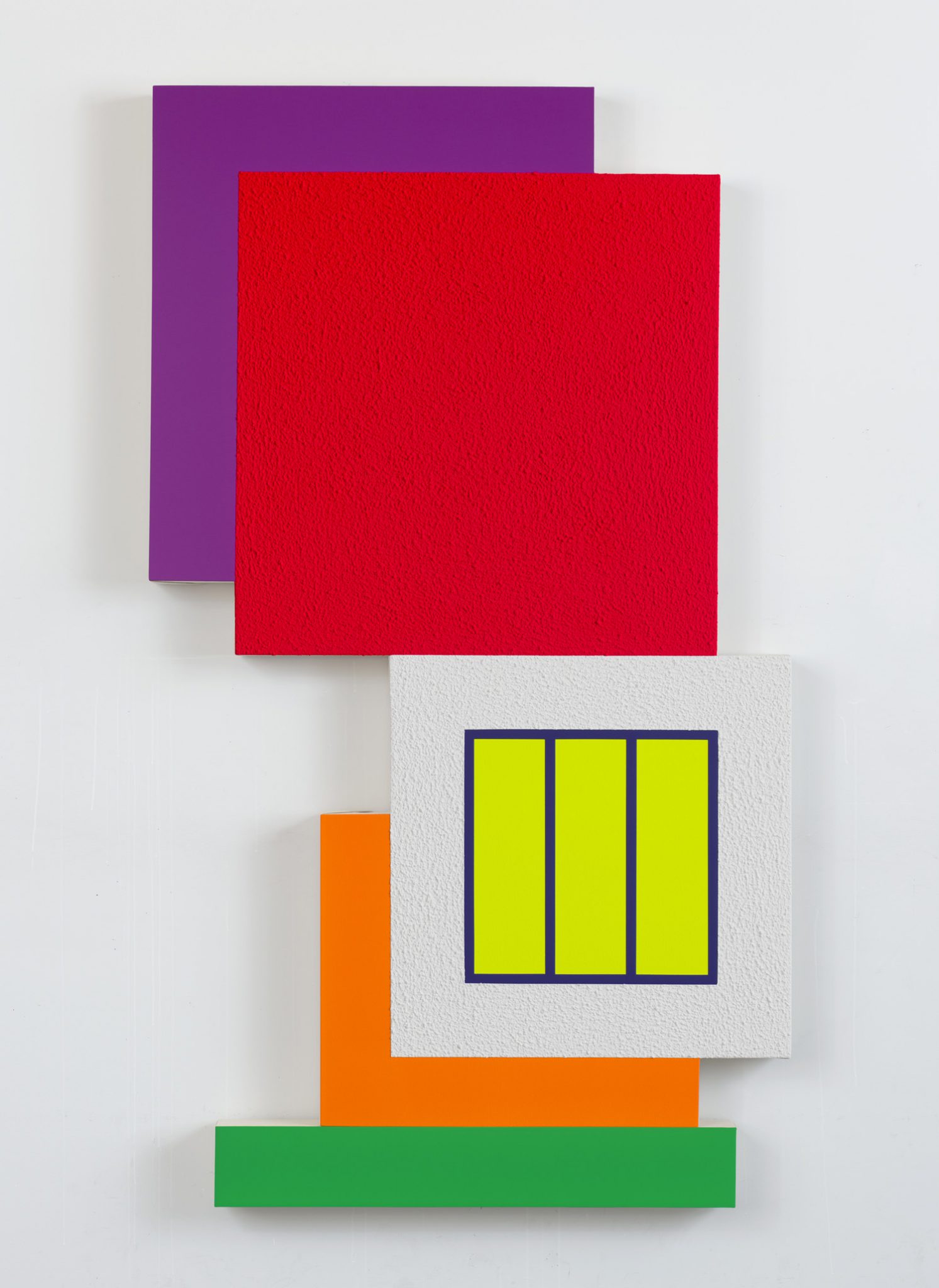

L: It is in this installation, that another major change, another revolution, occurred in your paintings: they were

no longer confined within a rectangular format and most of them now consist of multiple canvases that weave together multiple

spaces. When I first saw them, I thought of them as constructor paintings, since they are so architectural, built block by block.

Then an idea of ‘transformer’ paintings came to mind: the blocks seem to be moving, creating new combinations, and there is

something very blockbuster about them. Then, a friend of yours mentioned that you call them dancing paintings, and it made so

much sense. These new paintings are currently presented in Xippas gallery, building a whole Sci-Fi city. Could you please tell

me about this new body of work and the exhibition?

P: I was invited by Renos Xippas to do a straightforward show of seven paintings, in contrast to my complicated

installation in 2018. They were made in 2020 and 2021, and continue the ideas that you described beginning with my New York

show in 2019. I don’t think they are all dancing, but instability seems to be the theme here. They are all still balanced

on a stable horizontal pediment, but mist of them look like they could fall over in one direction or another. I guess I

wanted to reproduce a sense that we are on shaky ground. It is also an opportunity to play around with the structure and

propose a mosaical vision of reality. The paintings are made of cells and prisons, each of which inhabits its own space

juxtaposed with the next. I hope they create a constantly changing puzzle. In the older compositions, there are still a

few conduits, but as we discussed, they are on the way out. I like to think that there is also an alchemical dimension to

my paintings. A friend of mine mentioned that they incorporate an idea of magical transformation, as each element morphs

into its opposite. A cell is not only a prison, but also a refuge or a fortress in which one may recharge him or herself.

Confinement turns into openness, since there are always channels of communication flowing into the cells, whether they are

visible or not. Rigidity of structure results in symbolic flexibility. I was always trying to access the symbolic and to

forge variable meaning through more or less constant, invariable forms.

L: An obvious question, is there any connection with the pandemic in the most recent works?

P: Oh, I think all my work responds to at least one aspect of the pandemic, how people

became physically isolated but connected by means of predetermined technological pathways. Sometimes I think

this entire societal trend by which we have become isolated in front of your computers or phones was precipitated

by some primal human fear of contagion and plague. Everyone alive today is the offspring of those who survived

the myriad plagues that have decimated humanity over the millennia.

L: Starting in your essays of the 80s, isolation and confinement were the cornerstones of

your reflections which were largely inspired by Foucault.

P: I have revisited his writings recently, notably his discussion of the development

of strategies quarantine which he claims were more or less the foundational principle of urban planning

in the modern era. Foucault advances the interesting idea that natural law theory imagines a state of

nature to speak about an ideal law system, while a governor hopes for a pandemic in order to create a

perfect state. A plague becomes an opportunity to unravel the “mess”, a way to structure reality through

geometry, reinforcing surveillance and social control.

Heterotopia I, presented by Flash Art and the Academy of Fine Arts of Venice, 2019