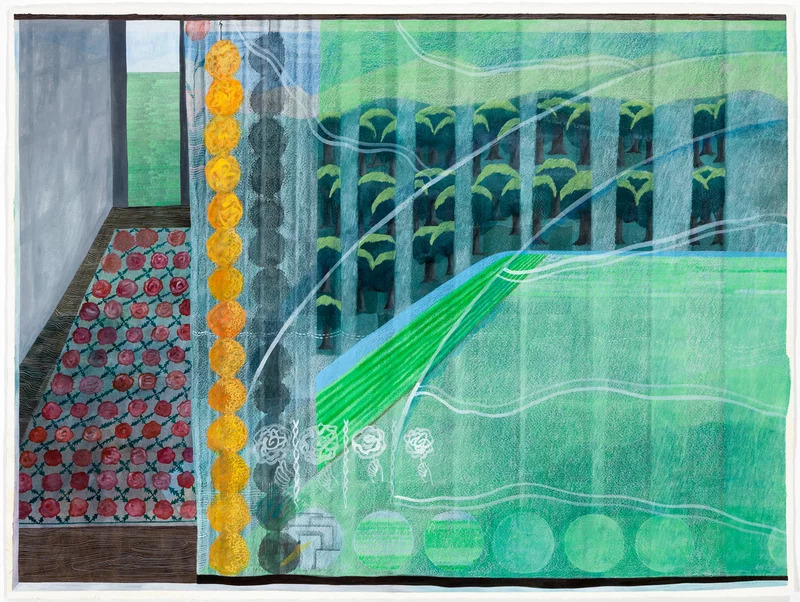

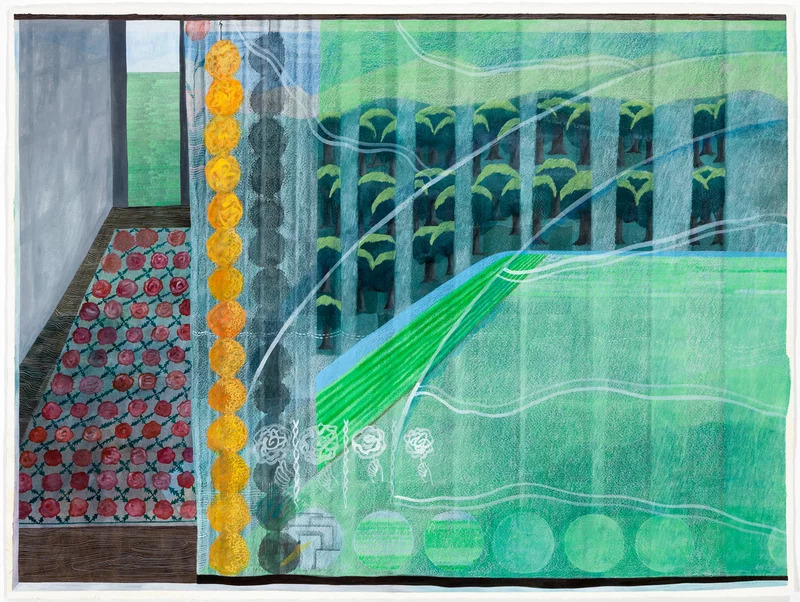

Mirror Curtains: Warmth and a Gift, 2016

Dreamscape - pre-winter, post-winter, 2018

A Forest, an Ocean and a Desert

Working steadily. Interlacing thread with thread, storyline with storyline. Slowly, patiently. Not painting but

weaving, – juxtaposing symbols and memories, faces and objects of thought. Weaving, but unlike Penelope, who

weaves to unweave. This is rather a ‘to weave’ type of weaving. So that symbols and memories, faces and objects of

thought, may be saved and remembered, now stored in a pictorial archive – a mythical reservoir? A symbolic space

that folds upon itself, making a fold within a fold within a fold… and transforming the act of painting into an act

of (un)folding. But in what sense (un)folding? First – collecting. Then – conserving the treasure: ars curandi.

Then, calling it forth - to breathe life into it. Inhale – exhale, and a pause in between….

…It is indeed both of weaving and folding/unfolding that we think of, when encountering the work of Karishma D’Souza.

Her artworks are so complex, that they recall ancient mappemondes, which they sometimes make reference to. They too

sought to fit the whole world on the sheet of paper or on a canvas. They too were meant to be unfolded (after being

unrolled) - path by path, river by river. The details in Karishma D’Souza’s artworks accumulate, multiply,

duplicate, like delicate leaves on a tree branch or threads woven into a tapestry. One may easily lose oneself in

contemplation, wandering among the elements and following the paths they trace, or, we can even say, constellations.

These elements are often interconnected and contextualized; they reference both texts (philosophic, poetic,

religious…) and situations (political, personal, archetypic…). “Layered with meaning”, they function as symbols in

which multiple realities and times coexist in a way that a part may reflect a whole - but also the whole universe -

much like Leibniz’s monads, which look into each other’s souls like metaphysical mirrors, to offer a glimpse of the

totality of the real, of course. Sometimes the elements spread across a single frame, as if cataloging the known

universe and discerning an order within it, even if this order is peculiar, akin to Borges’s fictitious taxonomy of

animals from “The Analytical Language of John Wilkins”[1] which divided creatures in “those belonging to the Emperor,

the embalmed ones, trained ones, ones suckling pigs”, etc., with the poetic arbitrariness of a chaotic orderliness.

Sometimes they create an alphabet, as in Rooting (2018). And sometimes, these elements reappear across different

artworks, linking them through invisible – like a spider’s web or transparent bridges.

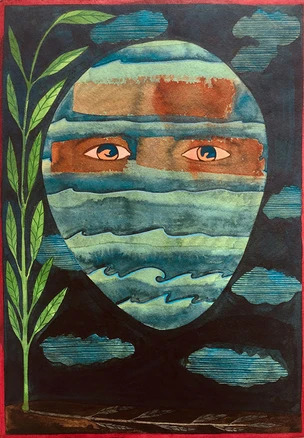

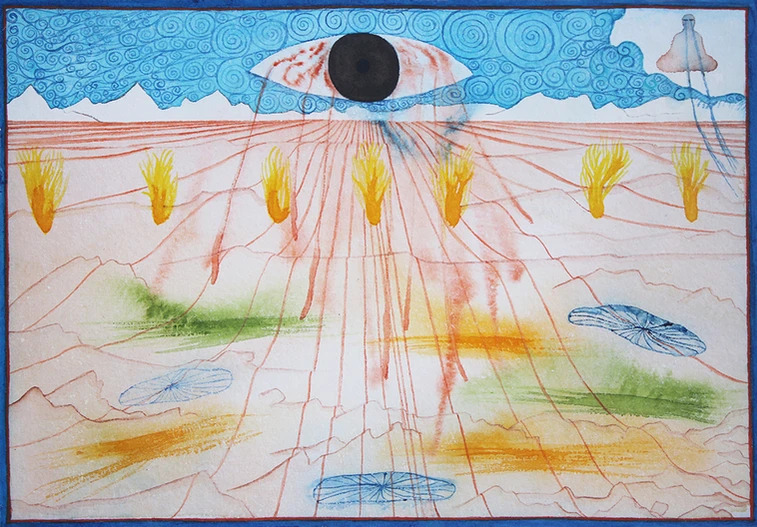

Raindrops and pebbles, rivers and oceans. Blood drops - they stand for human slayer. Dots of red mark the murdered.

Blue, like tears. Green, like plants. Yellow, like wasteland or like a desert. Reflecting one another, these signs

witness and record everything, so that one day they may testify, making the invisible visible and bringing justice

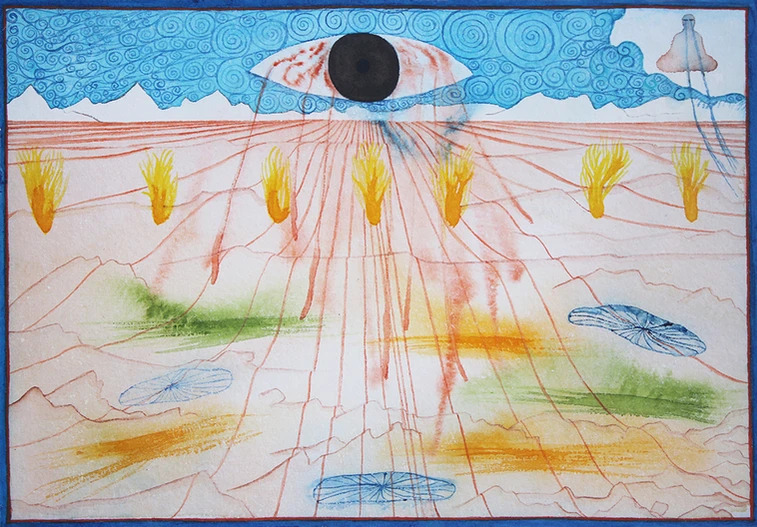

to those who have wronged. In Seeing: If There Was Sight: Kashmir, flames take on the role of witness: alluding to a verse by Rumi

(“Come in; and witness water blazing high, as fire / This is a world where flame like water is...”), they shed light

on the Kashmir rebellion of 2017, illuminating an image of a bleeding eye to ensure that neither peaceful men, women

and children, blinded by bullets, nor the officials who shot at them, are ever forgotten. By encrypting the story in

metonymic symbols, the work bypasses censorship without, however, minimizing the truth. One must only learn to read

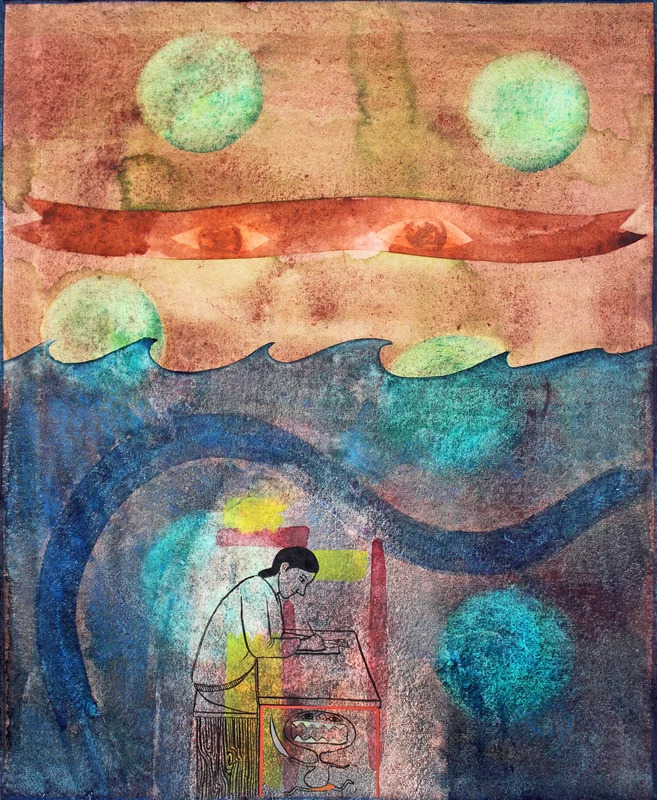

into it, decode it and listen (Hearing: Listening well one found solace). In Witness, the haunting eyes gaze

intensely outward - at the viewer – and inward - into themselves, to discover monsters lurking in the shadows or

hiding under a table. All these flames, eyes and ears, are here to witness, to hear. To speak for those who have

lost their voices – until they find the strength to stand for themselves once again.

Seeing: If There Was Sight: Kashmir, 2018

In the meanwhile, it is the artworks that are summoned to witness. Silently, but no less powerfully, they tell their

stories. Some are personal, even autobiographical – a memory of a parents’ house, a pebble, a window with a view.

Others are shared, alluding to the current political situation in India, the ecological crisis worldwide, or the

general rise in violence within socio-political systems. Yet both have something in common - they aim to reveal what

is universal: a hidden context, an archetypical layer of being in which everything is rooted. Our common ground. It

may be an experience – falling in love, lingering in between states or countries, suffering from injustice. It might

be a memory of a place or time. Sometimes, it is a feeling.

Hearing: Listening Well One Found Solace, 2018

As mentioned, certain elements reappear across artworks and create trans-pictorial narratives: such are constants,

empowered through revisitation and repetition. For example, there is the narrative of a forest, brought into focus

in paintings like This Forest, Memories of the Forest, the Red forest of the heart, etc. Ancient and timeless, the

forest is a place where one may reconnect with ancestors, returning to the origins and the immutable. Repetitive,

like a song or a prayer, it becomes a zone of meditation where a tree stands by a tree that stands by a tree… – try

counting them, like one counts breaths, one after another. Perhaps, this is why it’s easier to feel an alert

calmness within its territories, to be lulled into a state of serenity by murmur of leaves, like a child in the

nature’s cradle or a fetus in an ancient womb.

Memories of the Forest-3, 2018

The forest is often inhabited. Sometimes by ants (This Forest, This Forest: Anthills, building majestic anthills and creating tiny auto-organized

microcosms inside the macro-realm of the forest. Sometimes by spirits, like in Memory of the Forest-3, in Hungry

ghosts: the movement through the forest or in This Forest-5. These god-like entities seek to protect the forest, and don’t dissolve nor

disappear even when the trees are cut off or engulfed in flames, but remain – to ensure that the forest may re-grow,

rising from the dead and from the ashes - phoenix-like – bringing hope in the midst of destruction.

Hungry Ghosts: the Movement Through the Forest, 2019

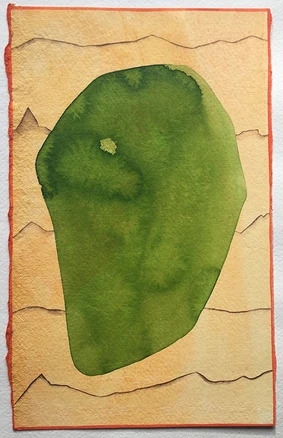

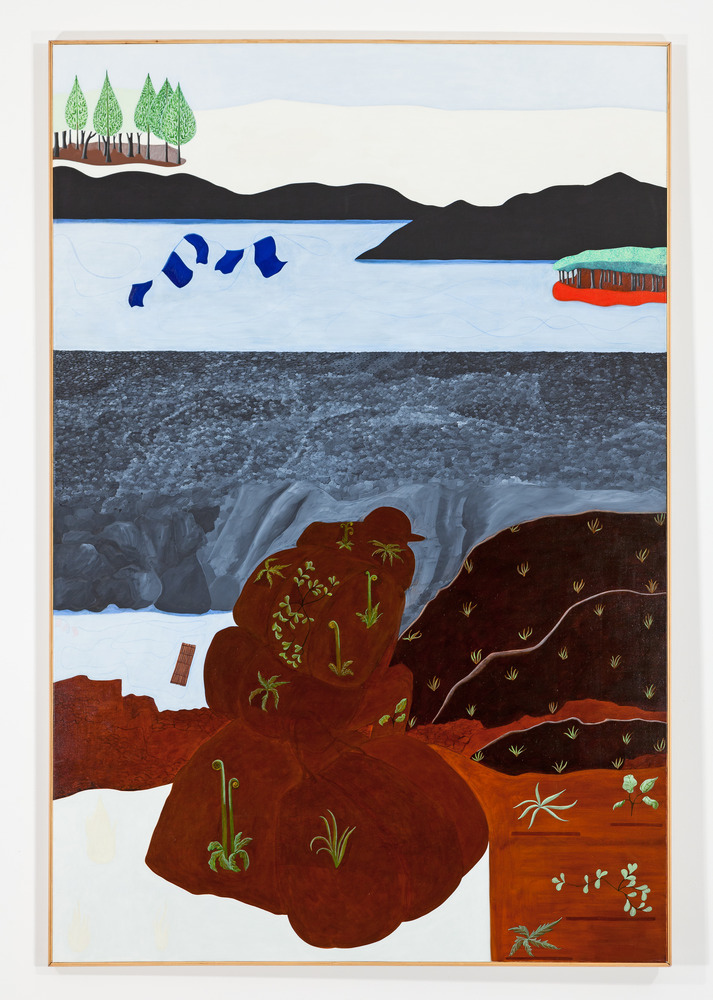

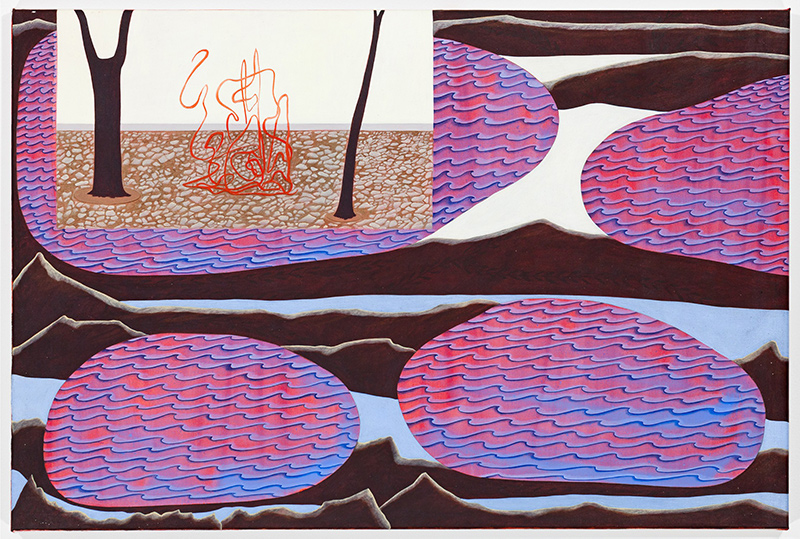

Another narrative is that of the ocean, emerging in the works of 2018-2019. Before this symbol appeared, the water

element was often represented through a river-symbol. In Rain Invocation (2014), Himalayan Landscapes: unseeing

(2016) or Lal Ded (2016), we mostly see rivers crossing green or rocky landscapes to bring life to wastelands.

Starting in 2018, a narrative of the ocean takes over, expanding the perspective far into the beyond.

Himalayan Landscapes: Unseeing, 2016

The ocean evokes the ideas of transgression and transformation, it speaks of journeys overseas, to remote parts of

the world. It becomes a portal into a mysterious terra incognita. Unlike the river which reveals the opposite bank,

the ocean conceals it, leaving only the promise of what lies ahead. The unknown world, world on the other side,

becomes a space for projection, inhabited by ghosts and fantasies, and, like all projections, it speaks more of what

resides within, rather than what waits ahead. In this sense, the ocean enables introspection, encouraging an inner

journey - towards the profound layers of the Self, often occurring in the face of the unknown. It disconnects,

carrying something (or oneself) away and creates a sense of alienation, yet allows to stay connected, as one

maintains the capacity to look back – through texts, mostly. Reading, too, is a form of travel (with a question at

the bottom of the well: what book would you bring along to the other side of the world?)

The Ocean Words aligns with this vision, offering a glimpse into personal depth and reflections on migration. Two

squares floating in the deep waters serve as abstract portraits of parents. Framing the painting like blood curtains

on a theater stage, two red trees ‘embrace’ the composition, evoking the idea of heritage: being capable to read the

past from the lips of the present. ‘Windows’ embedded in the trunks, featuring what resemble snapshots of a tree

represent memories mixed with perceptions (raising an almost Husserlian question – is it the same tree in each

frame? Or does a new one take place of the original each time we blink or look away?) In the central part of

composition, we see the ocean’s water, painted in three distinct ways and creating layers. The deepest layer

Imitates the ways of old manuscripts to represent water, the upper one, chaotic and expressive, mingles together

aquatic masses, suggesting the emergence of something new – of a new self maybe? The different modes of representing

water in this painting allude to the ways in which languages denote the same thing differently. The layers remain

distinct, like languages or cultures – transposed or transplanted through migratory processes – and never fully

merge, but rather encase one another, altering each other’s identities, while staying true to themselves. Learning

different languages/ layers/ ways of being deepens one’s understanding – not only of oneself but also of history,

revealing our profound inter-connectedness – across time and space. Our shared roots.

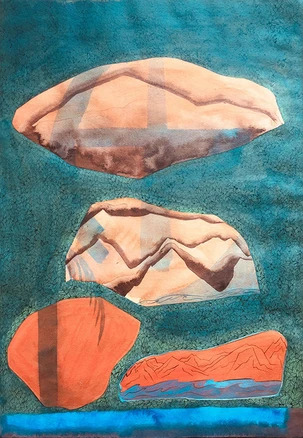

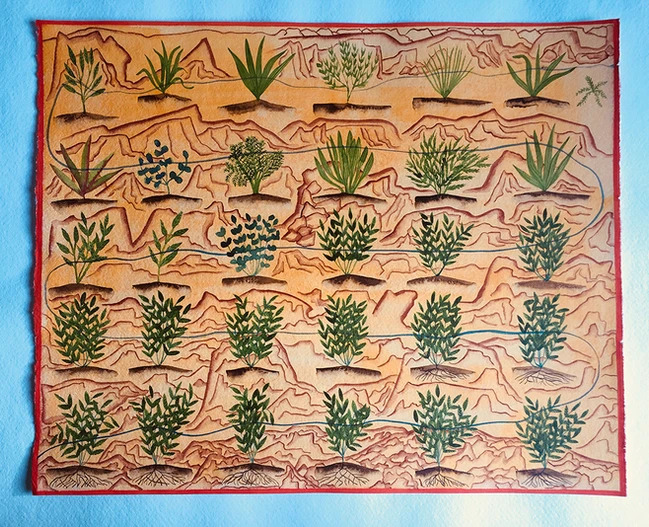

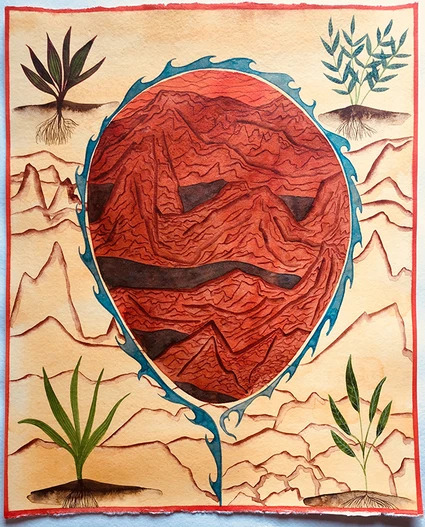

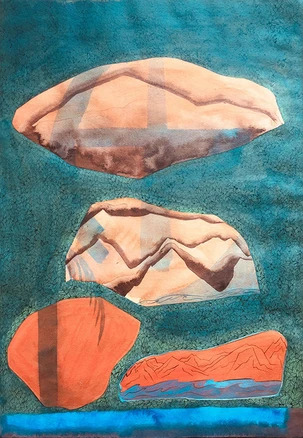

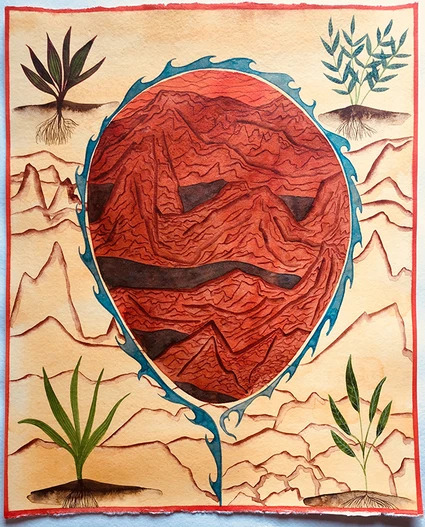

The narrative of the desert, which is also quite recent, could be seen as an expansion of an older storyline of the

rock and wasteland (for example in Land Conversations), nurtured in turn by reading of T.S. Eliot, the Bible and Robert Frost (Mending Wall). Similar to

how the river symbol evolves into the ocean, broadening the perspective, rocks and stones turn into a vast desert in

Rooting, The friend seen from a distance (2018) or the large-format painting Rooting-1. A mappa mundi of

memories and perceptions, this painting forms a sort of a mental collage that brings together objects and fragments

of landscapes belonging to different timelines and geographies. This work was made in Lisbon, where Karishma stayed

for an art residency, before deciding to settle there. Immersed in an unfamiliar context, in a foreign linguistic

environment without speaking the language, she began to absorb the visual vocabulary that Lisbon had to offer,

familiarizing herself with it through painting. Thus, the grey staircase alludes to the stairs of Lisbon,

omnipresent in the area where she had her studio. The desert references Africa, drawing our attention to Morocco,

the Sahara and the old Portuguese colonies.

The streets of Lisbon are often invaded by sand and dust brought by the sirocco winds from the Sahara. “Little things

travel fast”[2] - volatile, these particles even manage to cross the sea, bringing plant seeds along and giving them a

chance to integrate into an alien context, to take root in a new world. Having travelled so far from home, these

plants find a new one in Lisbon, which they slowly start to appropriate. They make us travel too, just by looking at

them - dreaming of unknown lands and of a desert. Sometimes, of a home too – since, in a dream, a desert may signify

a deserted space, why not a deserted home. A place where we no longer are and which keeps sending us messengers – a

mixture of seeds, dust and sand – as if to remind us of where we came from. Bringing nostalgia on their wings but

also a thought: a desert, too, can be a home; it, too, can generate life, whether within its territories – or by

sending something away, into the unknown.

The Friend Seen from a Distance, 2018

Revealing a strong desire to broaden up, a wish to cover more territories and subjects, Karishma’s recent works

mobilize expansive symbols, as if to clear space for something new. They create a sort of stage, a mental theater,

sometimes almost literally, like in Ocean Words, in which red trees reminiscent of curtains frame an aquatic theater

or in Depth to Recognize, where an earth-platform floats on ocean waters, resembling a stage. They open up a space

for reflection, introspection and observation, but also for action - for inner and outer transformation.

Something is happening within the frame: the pictorial space fills by spirits (Hungry Ghosts: Movement Through a

Forest), liquids (Heart Vessels: the road taken ) and phantoms of thoughts (Portals). There is a strong sense of movement,

whether it is the moving masses of water in Ocean Words or its terrestrial counterpart, the dust and seeds traveling

across the sea in Rooting-1. It is this transformative movement that makes these new artworks so engaged and

engaging.

As Karishma notes, her paintings used to be similar to static settings. Now, as their structure grows more complex,

they embrace movement and action. They still tell stories, but now they do more than that. They call forth – letting

things emerge from the deep waters of the collective unconscious and thus from oblivion – as if to say: some things

have to be remembered. This is why they continue their weaving: storyline by storyline, narrative thread by

narrative thread. This is why memories and signs, objects and objects of thought, are interlaced into a symbolic

tapestry. These works create a sort of a diary - a world’s diary – with multiple pages and hidden flowers tucked in

between.

Heart Vessels: the Road Taken, 2019

All images courtesy Xippas Paris and the artist

Born in 1983 in Mumbai, Karishma D'Souza lives and works in Lisbon, Portugal.

Karishma D’Souza graduated from University of Baroda in 2006. She did a two-year residency in Rijksakademie in Amsterdam in 2012-2013. In 2017, Karishma D’Souza was on residency in Skowhegan, Maine, USA, and in 2018 – in collective studio Concorde, Lisbon, Portugal.

Exhibitions (selection): Fundaçao Oriente of Fine Arts (Goa), Atelier Concorde (Lisbon), Dapiran Art Project Space (Amsterdam), Fondation of the India of Arts (Bangalore).

Public collections: CNAP, Paris, France, Chadha Art Collection (the Netherlands), Utrecht Central Museum (the Netherlands), Rijksakademie Van Beeldende Kunsten (the Netherlands).