Peter Halley

artpress n.510

More Than Geo

May 2023

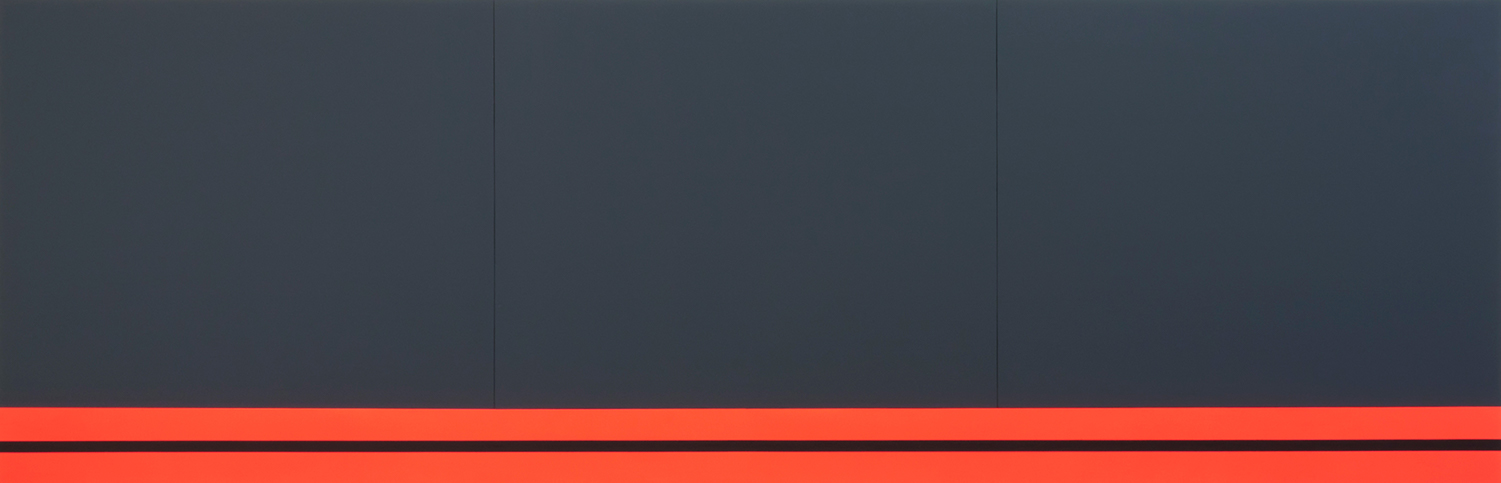

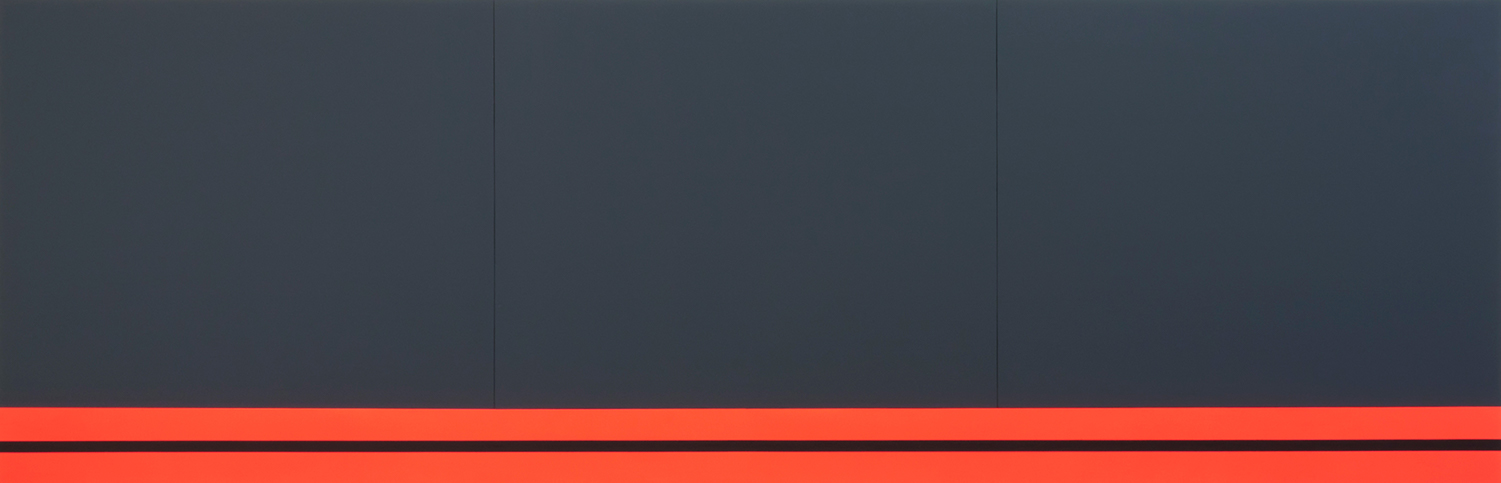

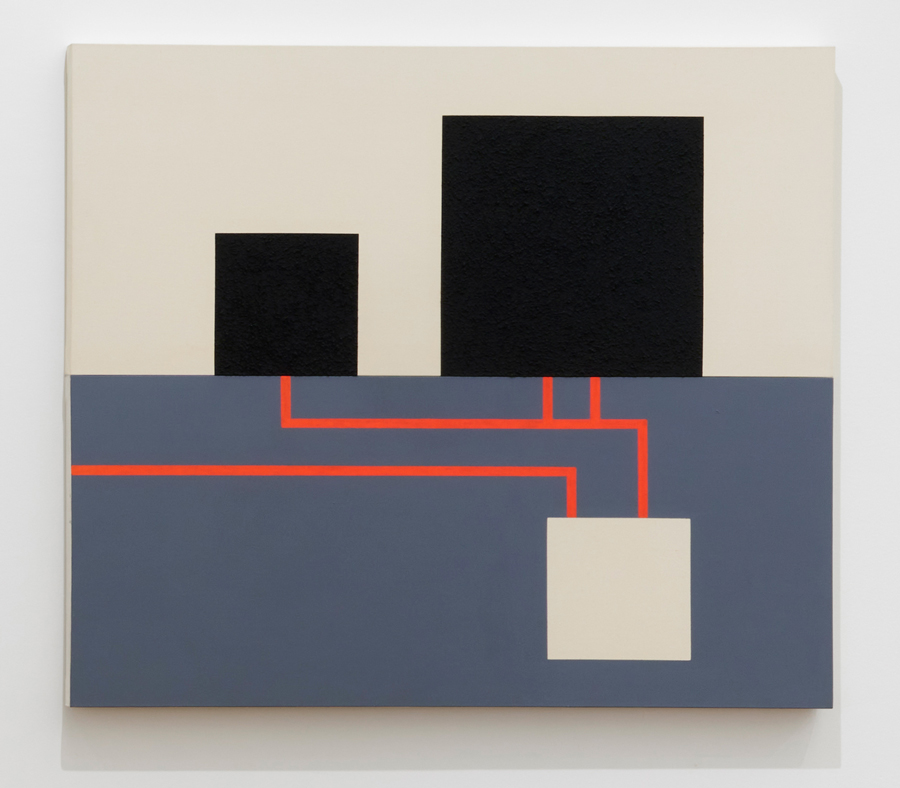

Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow, 1987

Baudrillard, the 1980s and the Parody

Imagine it’s the 80s. The Internet has not yet arrived on the scene to alter our everyday experience,

but the informational flux is already overwhelming (or should we say ‘exploding’?)

Television is ubiquitous. Personal computers too are gaining ground, migrating from offices to homes.

With technology becoming more and more autonomous, penetrating every layer of existence,

the very nature of reality itself “becomes abstract, both visually and physically”.[1]

Already replaced by its industrially shaped technological double (like a horse by a car,

a candle by electric light, etc.[2]), it is now either ‘piped in’[3] or reduced to a succession of models

of the post-industrial paradigm. Its poetry is that of a social security / credit card number,

its architecture is that of cubicles and conduits, and its language is a language of code[4]

(DNA et al.). A kingdom of lost referents built upon Baudrillard’s ‘desert of

reality’[5] to dissimulate its own desert-ness and absurdity.

In this superstructure, all is channeled and controlled by geometry,

starting with suburban environments (now agglomerations, ruled by seriality and anonymity[6]),

to the megapolises like New York (the very quintessence of a geometric state of mind).

People, products, thoughts, all confused, all together, travel through a system of circuits.

They circulate (carefully avoiding short circuits) through hallways and highways.

They surf through zeroes and ones in the totality of a Cartesian landscape. One might believe

oneself to be in the dystopian space of Godard’s Alphaville (1965): with a machine instead

of a heart and rules of logic instead of the law…

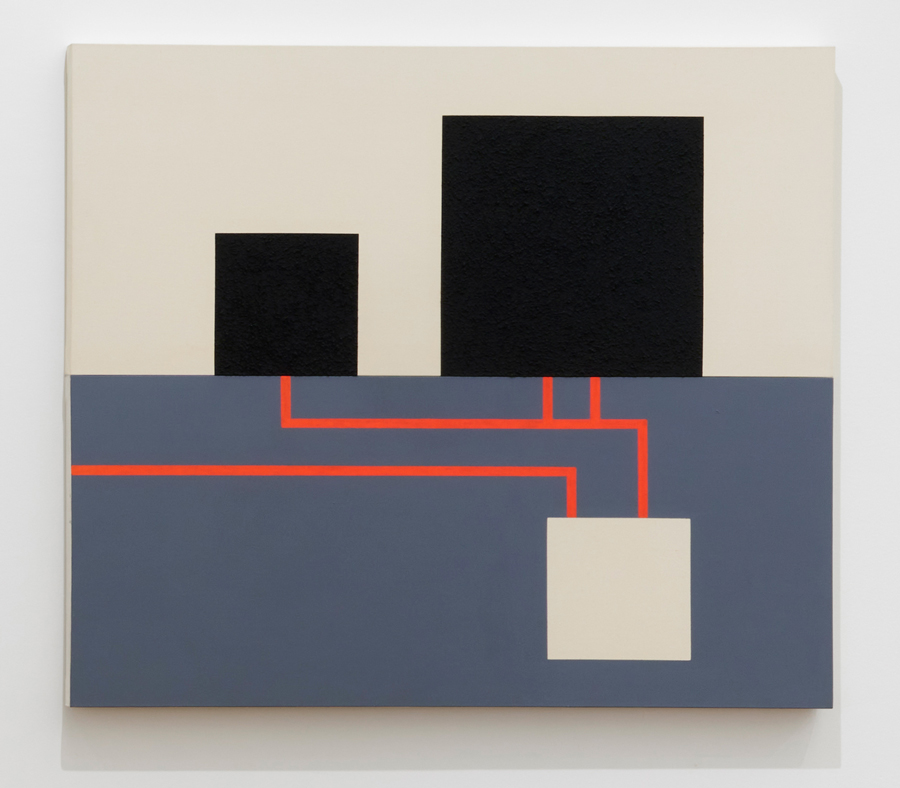

Two Cells with Conduit and Underground Chamber, 1983

Cell with Smokestack and Underground Conduit, 1985

Contrary to what is sometimes believed, the 80s were rather dark times (between the massive unemployment

of the early years, the eruption of AIDS and Ronald Reagan coming to power, it wasn’t much fun at all).

A state of crisis felt both imminent and permanent, and its artificial on-going-ness was already

qualified as “necessary” by Baudrillard. The air was even more suffocating than before, with

the (hyper)realization that the Foucauldian prison was actually not confined to a particular place.

Despite all this going on, a large part of the art world seemed to keep dreaming about

auto-referentiality and spirituality, fueling it with the sense of non-involvement and detachment.

And that’s the moment Peter Halley stepped onto the scene with a different strategy in mind and

suggested focusing on the context instead of ignoring it. It was as brilliant as it was radical.

Truly, a Copernican revolution. And, like all revolutions, it demanded a patricide. Disenchanted

with abstract expressionism and minimalism, Peter Halley brought them back to earth, insisting

that even the most escapist fantasies, the most auto-referential worlds, were, in fact, produced

by ideology and were secretly (and usually unconsciously) promoting it. Thus, there was no promised

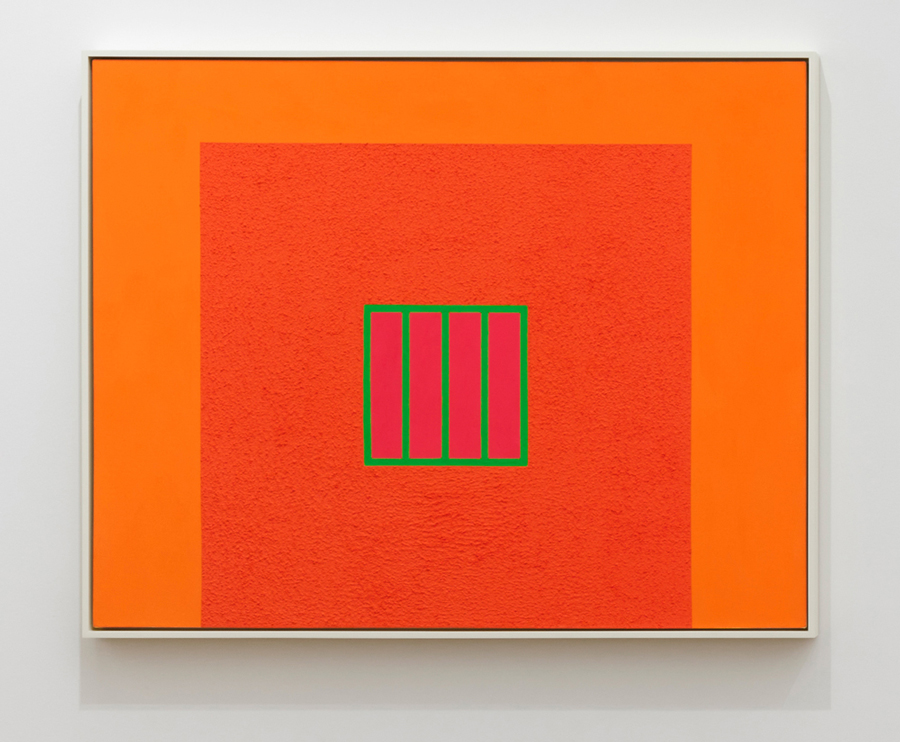

liberation through abstraction, no esoteric meaning beyond it. A square is a cell (sometimes a prison)[7].

Its mysticism is cheap (one could hear Robert Smithson’s ‘ha-ha’[8] from his Generalized Laughter Theory

in the background). Moreover, these were the same forces that shaped literally everything, including suburbia,

with its repetitive middle-class houses, all covered in stucco (what was original and liberating about that?).

Besides, meaning had already drowned in the ponderous flux of information[9], leaving us with one

single possible strategy: parody. And it is precisely this logic that translated the idea of a prison

into a square with bars – Peter Halley’s iconic image.

Peter Halley’s show Conduits, currently on view at the Mudam in Luxembourg,

speaks of those times, the 80s. The paintings are dark and powerful, but also funny, with their

goofy prisons and cartoonish houses (and what’s up with the proto-conduit pointing at the sky in

the “Smokestack Paintings” – where is it sending its message? straight to heaven?). The cells

glow, pulsating with energy. The underground conduits run in straight lines, recreating the

frozen heartbeat of the city, while pumping life into it. A symphony of technology and the

artificial, of connectivity and confinement. Wait, we are still talking about the 80s…

is it right?

All images courtesy the artist and MUDAM, Luxembourg

Born in 1953 in New York, USA, Peter Halley lives and works in New York.

Peter Halley had numerous institutional shows: CAPC Musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux (1991), Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid (1992), Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (1992), Des Moines Art Center (1992), Dallas Museum of Art (1995), Museum of Modern Art, New York (1997), Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art (1998), Museum Folkwang, Essen (1998), Butler Institute of American Art (1999), Disjecta interdisciplinary Art Center, Portland (2012), Musée d’art moderne et contemporain de Saint-Étienne Métropole (2014), Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt (2016), The Lever House Art Collection, New York (2018), Museo Nivola, Sardinia and The Ranch, Montauk (2021), Dallas Contemporary, Texas (2021-2022).